more about .....

Endothelial Cells

by Professor John McGeachie

Introduction

All blood vessels and lymphatics are lined by endothelial cells; the layer being called the endothelium. These extraordinary cells were once considered to be simple lining cells with very few functional roles, other than to keep cells within the blood from leaking out of the vessels. However, for some years research on endothelial cells has revealed that they have an amazing array of functional and adaptive qualities. Moreover, they are the key determinants of health and disease in blood vessels and play a major role in arterial disease.

Structure

Structure

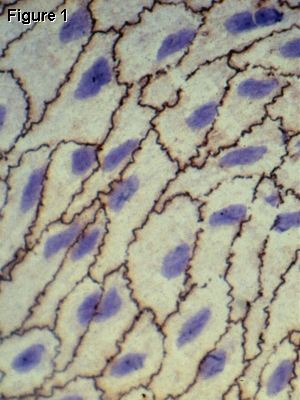

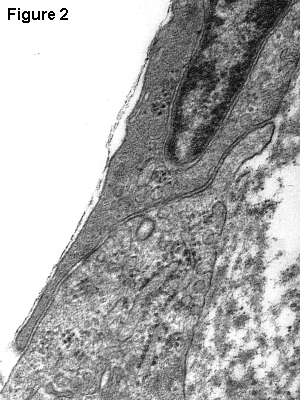

Endothelial cells are very flat, have a central nucleus, are about 1-2 µm thick and some 10-20 µm in diameter. They form flat, pavement-like patterns on the inside of the vessels and at the junctions between cells there are overlapping regions which help to seal the vessel (see Figure 1, a surface preparation of arterial endothelium). The blue endothelial nuclei are obvious and the cell boundaries are stained black with silver nitrate. The dark lines show the intercellular junctions. These intercellular junctions are critical for the integrity of the vessel. Figure 2 shows an electron micrograph of two endothelial cells overlapping. Toxic substances, such as nicotine, open up these junctions and allow large molecules to pass through the wall. Thus such toxins can potentiate degenerative changes in blood vessels and lead to serious disease (known as vascular disease). The cytoplasm is relatively simple with few organelles, mostly concentrated in the perinuclear zone. The most obvious feature is the concentration of small vesicles (pinocytotic vesicles) adjacent to the endothelial cell membranes. This is a mechanism for passing materials, especially fluid, across the cells from the blood stream to the underlying tissues. Gases simply diffuse through very rapidly, and this is exemplified in the lung capillaries where there is very efficient movement of gases (carbon dioxide, oxygen and anaesthetics etc).

In some capillaries the

endothelium is punctuated and has apparent holes or fenestrae ("windows") which allow for the rapid

passage of large molecules (as in endocrine glands) or huge amounts

of fluid (as in the kidney). In other organs the endothelium is

very tightly sealed and there is highly selective transport across

the membranes, as occurs in the brain as part of the blood-brain barrier.

In some capillaries the

endothelium is punctuated and has apparent holes or fenestrae ("windows") which allow for the rapid

passage of large molecules (as in endocrine glands) or huge amounts

of fluid (as in the kidney). In other organs the endothelium is

very tightly sealed and there is highly selective transport across

the membranes, as occurs in the brain as part of the blood-brain barrier.

Function

Endothelial cells are selective filters which regulate the passage of gases, fluid and various molecules across their cell membranes. Different organs have different types of endothelium: some leaky and some very tightly bound.

The most exciting development in our understanding of endothelial cells concerns the knowledge of the cell surface molecules. These act as receptors and interaction sites for a whole host of important molecules, especially those that attract or repel white blood cells (leucocytes). Leucocyte adhesion molecules are important in inflammation and whilst these are normally repelled by endothelium, in order to allow the free flow of blood cells over the surface, in inflammatory states the leucocytes are actually attracted to the endothelium by adhesion molecules. They then pass through the endothelial cells by a process called diapedesis, which literally means "walking through" (the endothelial cell). Many leucocytes pass through endothelial cells, especially in capillaries as part of their normal life cycle, so that they can monitor foreign agents (antigens) in the tissues. Macrophages (scavenger cells) are mostly derived from monocytes, which are leucocytes produced in the bone marrow, travel in the blood and pass through endothelial cells to gain access to various tissues of the body.

Another vitally important molecule synthesized in endothelial cells is Factor VIII, or von Willibrand's Factor. This is essential for the blood clotting reaction (haemostasis). In some unfortunate individuals there is a genetic absence of this factor, and it leads to the life-threatening disorder called haemophilia, where the sufferer may bleed to death from a simple scratch. Fortunately, Factor VIII can be administered to haemophiliacs at a time of crisis and the condition controlled.

Endothelial cells are also responsive to local agents such as histamine, which is released when local tissues are damaged. Consequently, the endothelial cells open up their intercellular junctions and allow the passage of large amounts of fluid from blood plasma so that the surrounding tissues become engorged with fluid and swollen: a condition called oedema. At the same time large numbers of leucocytes, escape and flood into the tissues. These events are the hallmarks of the inflammatory response. It is exemplified by a simple scratch on the skin or a splinter wound: the area quickly becomes reddened (opening up of capillaries) and swollen (oedema).

Pathology

Arterial disease is one of the greatest causes of morbidity (tissue damage and disability) and mortality (death) in the Western World. Whilst the incidence of death from this condition is decreasing (due to better education, diet, smoking reduction and life-style changes), it is still a major health problem. Endothelial cells play a crucial role in the initiation (pathogenesis) of arterial disease. The commonest form of disease is arteriosclerosis (literally "hardening of the arteries"). This may be due to a number of factors but the most common is the deposition of cholesterol in the sub-endothelial layer of arteries. It has long been realised that the endothelial cells become "injured" either physically by abrasion or toxic insult (such as from nicotine) and large molecules, which are normally confined to the blood, are allowed to escape through the endothelium and become lodged in the smooth muscle cells in the arterial wall. Macrophages also pass through and accumulate fat (lipid and cholesterol) deposits. The most common name for this disease is atherosclerosis. This process is very slow, but there is a gradual accumulation of this fatty and fibrous material which not only makes the normally elastic artery hard (sclerotic) but the deposits, known as "plaques" may encroach on the arterial lumen and cause turbulent blood flow. This may lead to a narrowing of the artery (stenosis) and facilitate the formation of a blood clot (thrombosis). Such serious consequences occur in "heart attacks" where the coronary arteries become narrowed or blocked. Likewise, in some strokes where arteries in the brain (cerebral arteries) become blocked by blood clots or atherosclerotic debris. This may originate from the large arteries in the neck (carotids) which shed off material from a plaque which rapidly passes into the cerebral arteries and blocks the vessel which has the same lumenal size as the debris. This causes death of the part of the brain normally supplied by the artery and the damage will depend upon which part of the brain is affected.

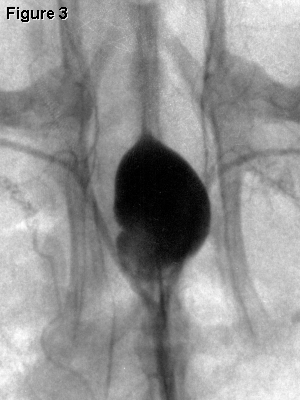

Another common degenerative

condition in arteries is called an

aneurysm, where the vessel wall becomes weakened by disease

or develops as a result a genetic deficiency in the structure. The

artery becomes swollen and may rupture, causing a major crisis if

the ruptured aneurysm occurs in a vital vessel, such as the aorta

or a cerebral artery (see Figure 3, a radiograph of an aneurysm in

an artery: the aneurysm is the black swelling in the centre of the

picture).

Another common degenerative

condition in arteries is called an

aneurysm, where the vessel wall becomes weakened by disease

or develops as a result a genetic deficiency in the structure. The

artery becomes swollen and may rupture, causing a major crisis if

the ruptured aneurysm occurs in a vital vessel, such as the aorta

or a cerebral artery (see Figure 3, a radiograph of an aneurysm in

an artery: the aneurysm is the black swelling in the centre of the

picture).

In summary, endothelial cells play a vital role in the health

and integrity of every tissue of the body because, apart from

cartilage, every cell lies within a few µm of a capillary.

These fine vessels are only 10-15 µm and consist merely of

endothelial cells and a very fine layer of adjacent material, known

as the basal lamina.

Blue Histology - Vascular System

Blue Histology - Vascular System