Motion, as a reaction of multicellular organisms to changes in the internal and external environment, is mediated by muscle cells.

The basis for motion mediated by muscle cells is the conversion of chemical energy (ATP) into mechanical energy by the contractile apparatus of muscle cells. The proteins actin and myosin are part of the contractile apparatus. The interaction of these two proteins mediates the contraction of muscle cells. Actin and myosin form myofilaments arranged parallel to the direction of cellular contraction.

A further specialisation of muscle cells is an excitable cell membrane which propagates the stimuli which initiate cellular contraction.

Three structurally and functionally distinct types of muscle are found in vertebrates:

- smooth muscle,

- skeletal muscle and

- cardiac muscle.

- Smooth muscle consists of spindle shaped cells of variable size.

The largest smooth muscle cells occur in the uterus during pregnancy (12x600 µm). The smallest are found around small arterioles (1x10 µm).

- Smooth muscle cells contain one centrally placed nucleus.

The chromatin is finely granular and the nucleus contains 2-5 nucleoli.

- The innervation of smooth muscle is provided by the autonomic nervous system.

- Smooth muscle makes up the visceral or involuntary muscle.

Structure of smooth muscle

In the cytoplasm, we find longitudinally oriented bundles of the myofilaments actin and myosin. Actin filaments insert into attachment plaques located on the cytoplasmic surface of the plasma membrane. From here, they extend into the cytoplasm and interact with myosin filaments. The myosin filaments interact with a second set of actin filaments which insert into intracytoplasmatic dense bodies. From these dense bodies further actin filaments extend to interact with yet another set of myosin filaments. This sequence is repeated until the last actin filaments of the bundle insert into attachment plaques .

.

In principle, this organisation of bundles of myofilaments, or myofibrils, into repeating units corresponds to that in other muscle types. The repeating units of different myofibrils are however not aligned with each other, and myofibrils do not run exactly longitudinally or parallel to each other through the smooth muscle cells. Striations, which reflect the alignment of myofibrils in other muscle types, are therefore not visible in smooth muscle.

Smooth endoplasmatic reticulum is found close to the cytoplasmatic surface of the plasma membrane. Most of the other organelles tend to accumulate in the cytoplasmic regions around the poles of the nucleus. The plasma membrane, cytoplasm and endoplasmatic reticulum of muscle cells are often referred to as sarcolemma, sarcoplasm, and sarcoplasmatic reticulum.

During contraction, the tensile force generated by individual muscle cells is conveyed to the surrounding connective tissue by the sheath of reticular fibres. These fibres are part of a basal lamina which surrounds muscle cells of all muscle types. Smooth muscle cells can remain in a state of contraction for long periods. Contraction is usually slow and may take minutes to develop.

Origin of smooth muscle

Smooth muscle cells arise from undifferentiated mesenchymal cells. These cells differentiate first into mitotically active cells, myoblasts, which contain a few myofilaments. Myoblasts give rise to the cells which will differentiate into mature smooth muscle cells.

Types of smooth muscle

Two broad types of smooth muscle can be distinguished on the basis of the type of stimulus which results in contraction and the specificity with which individual smooth muscle cells react to the stimulus:

- The multiunit type represents functionally independent smooth muscle cells which are often innervated by a single nerve terminal and which never contract spontaneously (e.g. smooth muscle in the walls of blood vessels).

- The visceral type represents bundles of smooth muscle cells connected by GAP junctions, which contract spontaneously if stretched beyond a certain limit (e.g. smooth muscle in the walls of the intestines).

- Skeletal muscle consists of very long tubular cells (also called muscle fibres).

The average length of skeletal muscle cells in humans is about 3 cm (sartorius muscle up to 30 cm, stapedius muscle only about 1 mm). Their diameters vary from 10 to 100 µm.

- Skeletal muscle fibres contain many peripherally placed nuclei.

Up to several hundred rather small nuclei with 1 or 2 nucleoli are located just beneath the plasma membrane.

- Skeletal muscle fibres show in many preparations characteristic cross-striations. It is therefore also called striated muscle.

- Skeletal muscle is innervated by the somatic nervous system.

- Skeletal muscle makes up the voluntary muscle.

Structure of skeletal muscle

Muscle fibres in skeletal muscle occur in bundles, fascicles, which make up the muscle. The muscle is surrounded by a layer of connective tissue, the epimysium, which is continuous with the muscle fascia. Connective tissue from the epimysium extends into the muscle to surround individual fascicles (perimysium) from which a delicate network of reticular fibres surrounds each individual muscle fibre (endomysium). The connective tissue transduces the force generated by the muscle fibres to the tendons.

The insertion into the tendon of the connective tissue fibres

surrounding the muscle fibres, i.e. the muscle-tendon

junction, is shown in one of the Lab sections on the connective

tissue page. It may be a good idea to take another look at the section.

Origin of skeletal muscle

The myoblasts of all skeletal muscle fibres originate from the paraxial mesoderm. Myoblasts undergo frequent divisions and coalesce with the formation of a multinucleated, syncytial muscle fibre or myotube. The nuclei of the myotube are still located centrally in the muscle fibre. In the course of the synthesis of the myofilaments/myofibrils, the nuclei are gradually displaced to the periphery of the cell.

Satellite cells are small cells which are closely apposed to muscle fibres within the basal lamina which surrounds the muscle fibre. Their nuclei are slightly darker than those of the muscle fibre. Satellite cells are believed to represent persistent myoblasts. They may regenerate muscle fibres in case of damage.

- Suitable Slides

- Sections of skeletal muscle, tongue or upper oesophagus - H&E

The spatial relation between the filaments that make up the myofibrils within skeletal muscle fibres is highly regular. This regular organisation of the myofibrils gives rise to the cross-striation, which characterises skeletal and cardiac muscle. Sets of individual "stria" within a myofibril correspond to the smallest contractile units of skeletal muscle, the sarcomeres.

Depending on the distribution and interconnection of myofilaments a number of "bands" and "lines" can be distinguished in the sarcomeres  :

:

I-band - actin filaments,

I-band - actin filaments,

A-band - myosin filaments which may overlap with actin filaments,

H-band - zone of myosin filaments only (no overlap with actin filaments) within the A-band,

Z-line - zone of apposition of actin filaments belonging to two neighbouring sarcomeres (mediated by a protein called alpha-actinin),

M-line - band of connections between myosin filaments (mediated by proteins, e.g. myomesin, M-protein).

The average length of a sarcomere is about 2.5 µm (contracted ~1.5 µm, stretched ~3 µm).

The protein titin extends from the Z-line to the M-line. It is attached to the Z-line and the myosin filaments. Titin has an elastic part which is located between the Z-line and the M-band. It contributes to keeping the filaments of the contractile apparatus in alignment and to the passive stretch resistance of muscle fibres. Other cytoskeletal proteins interconnect the Z-lines of neighbouring myofibrils. They also connect the Z-lines of the peripheral myofibrils to the sarcolemma.

The area of contact between the end of a motor nerve and a skeletal muscle cell is called the motor end plate. Numerous fine branches of the motor nerve make plate-like contacts (boutons) with the muscle cell. The excitatory transmitter at the motor end plate is acetylcholine. The space between the boutons and the muscle fibre is called primary synaptic cleft. Numerous infoldings of the sarcolemma in the area of the motor end plate form secondary synaptic clefts.

The spread of excitation over the sarcolemma is mediated by voltage-gated ion channels.

Invaginations of the sarcolemma form the T-tubule system which "leads" the excitation into the muscle fibre, close to the border between the A- and I-bands of the myofibrils. Here, the T-tubules are in close apposition with cisternae formed by the sarcoplasmatic reticulum. This association is called a triad.

Voltage-sensitive channels in the walls of the T-tubules (dihydropyridine (DHP) receptors) allow small amounts of calcium to enter the sarcoplasm of the muscle fibre. This influx mediates the efflux of calcium from the sarcoplasmatic reticulum through calcium-sensitive calcium channels (ryanodine receptors).

Sites of interaction between actin and myosin are in resting muscle cells "hidden" by tropomyosin. Tropomyosin is kept in place by a complex of proteins collectively called troponin. The binding of calcium to troponin-C induces a conformational change in the troponin-tropomyosin complex which permits the interaction between myosin and actin and, as a consequence of this interaction, contraction.

ATP-dependent calcium pumps in the membrane of the sarcoplasmatic reticulum typically restore the concentration of Ca to resting levels within 30 milliseconds after the activation of the muscle fibre.

Skeletal muscle cells respond to stimulation with a brief maximal contraction - they are of the twitch type. Individual muscles fibres cannot maintain their contraction over longer periods. The sustained contraction of a muscle depends on the "averaged" activity of often many muscles fibres, which individually only contract for a brief period of time.

The force generated by the muscle fibre does depend on its state of contraction at the time of excitation. Excitation frequency and the mechanical summation of the force generated is one way to graduate the force generated by the entire muscle. Another way is the regulation of the number of muscle fibres which contract in the muscle. Additional motor units, i.e. groups of muscle fibres innervated by one nerve fibre and its branches, are recruited if their force is required. The functional properties of the muscle can be "fine-tuned" further to the tasks the muscle performs by blending functionally different types of muscle fibres:

- Red or type I fibres

-

Red muscles contain predominantly (but not exclusively) red muscle cells. Red muscle cells are comparatively thin and contain large amounts of myoglobin and mitochondria. Red fibres contain an isoform of myosin with low ATPase activity, i.e. the speed with which myosin is able to use up ATP. Contraction is therefore slow. Red muscles are used when sustained production of force is necessary, e.g. in the control of posture.

- White or type II fibres

-

White muscle cells, which are predominantly found in white muscles, are thicker and contain less myoglobin. ATPase activity of the myosin isoform in white fibres is high, and contraction is fast. Type IIa fibres contain many mitochondria and are available for both sustained activity and short-lasting, intense contractions. Type IIb fibres contain only few mitochondria. They are recruited in the case of rapid accelerations and short lasting maximal contraction. Type IIb fibres rely on anaerobic glycolysis to generate the ATP needed for contraction.

Skeletal muscle fibres do not contract spontaneously. Skeletal muscle fibres are not interconnected via GAP junctions but depend on nervous stimulation for contraction. All muscle fibres of a motor unit are of the same type.

Fibre type is determined by the pattern of stimulation of the fibre, which, in turn, is determined by the type of neuron which innervates the muscle. If the stimulation pattern is changed experimentally, fibre type will change accordingly. This is of some clinical / pathological importance. Nerve fibres have the capacity to form new branches, i.e. to "sprout", and to re-innervate muscle fibres, which may have lost their innervation as a consequence of an acute lesion to the nerve or a neurodegenerative disorder. The type of the muscle fibre will change if the type of stimulation provided by the sprouting nerve fibre does not match with the type of

muscle. The process of reinnervation and type adjustment may result in fibre type grouping within the muscle, i.e. large areas of the muscle are populated by muscle fibres of one type.

Muscle spindles are sensory specialization of the muscular tissue. A number of small specialised intrafusal muscle fibres (nuclear bag fibres and nuclear chain fibres) are surrounded by a capsule of connective tissue. The intrafusal fibres are innervated by efferent motor nerve fibres. Afferent sensory nerve fibres surround the intrafusal muscle fibres.

Muscle spindles are sensory specialization of the muscular tissue. A number of small specialised intrafusal muscle fibres (nuclear bag fibres and nuclear chain fibres) are surrounded by a capsule of connective tissue. The intrafusal fibres are innervated by efferent motor nerve fibres. Afferent sensory nerve fibres surround the intrafusal muscle fibres.

If the muscle is stretched, the muscle fibres in the muscle spindle are stretched, sensory nerves are stimulated, and a change in contraction of the muscle is perceived. Different types of intrafusal fibres and nerve endings allow the perception of position, velocity and acceleration of the contraction of the muscle.

The contraction of the intrafusal fibres, after stimulation by the efferent nerve fibres, may counteract or magnify the changes imposed on the muscle spindle by the surrounding muscle. The intrafusal fibres and the efferent nerves can in this way set the sensitivity for the sensory nerve ending in the muscle spindle.

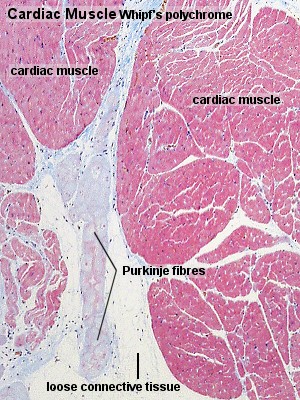

- Cardiac muscle consists of muscle cells with one centrally placed nucleus.

Nuclei are oval, rather pale and located centrally in the muscle cell which is 10 - 15 µm wide.

- Cardiac muscle is innervated by the autonomic nervous system.

- Cardiac muscle exhibits cross-striations.

- Cardiac muscle is for these reasons also called involuntary striated muscle.

Structure of cardiac muscle

The ultrastructure of the contractile apparatus and the mechanism of contraction largely correspond to that seen in skeletal muscle cells. Although equal in ultrastructure to skeletal muscle, the cross-striations in cardiac muscle are less distinct, in part because rows of mitochondria and many lipid and glycogen droplets are found between myofibrils.

In contrast to skeletal muscle cells, cardiac muscle cells often branch at acute angles and are connected to each other by specialisations of the cell membrane in the region of the intercalated discs. Intercalated discs invariably occur at the ends of cardiac muscle cells in a region corresponding to the Z-line of the myofibrils (the last Z-line of the myofibril within the cell is "replaced" by the intercalated disk of the cell membrane). In the longitudinal part of the cell membrane, between the "steps" typically formed by the intercalated disk, we find extensive GAP

junctions.

T-tubules are typically wider than in skeletal muscle, but there is only one T-tubule set for each sarcomere, which is located close to the Z-line. The associated sarcoplasmatic reticulum is organised somewhat simpler than in skeletal muscle. It does not form continuous cisternae but instead an irregular tubular network around the sarcomere with only small isolated dilations in association with the T-tubules.

Cardiac muscle does not contain cells equivalent to the satellite cells of skeletal muscle. Therefore cardiac muscle cannot regenerate.

- Suitable Slides

- Sections of cardiac muscle - Alizarin Blue, Whipf's polychrome, iron haematoxylin, H&E

Excitation in cardiac muscle

In theory, a stimulus can be propagated throughout the muscular tissue by way of the GAP junctions between individual muscle cells. A further system of modified cardiac muscle cells, Purkinje fibres, has developed, which conduct stimuli faster than ordinary cardiac muscle cells (2-3 m/s vs. 0.6 m/s), and which ensure that the contraction of the atria and ventricles takes place in the order that is most appropriate to the pumping function of the heart. Purkinje fibres contain fewer myofibrils than ordinary cardiac muscle cells. Myofibrils are mainly located in the periphery of the cell. Purkinje fibres are

also thicker than ordinary cardiac muscle cells.

Modified muscle cells in nodal tissue (nodal muscle cells or P cells; P ~ pacemaker or pale-staining) of the heart exert the pacemaker function that drives the Purkinje cells. The rhythm generated by the nodal muscle cells can be modified by the autonomic nervous system, which innervates the nodal tissue and accelerates (sympathetic) or decelerates (parasympathetic) heart rate.

![]() .

.

Muscle spindles are

Muscle spindles are