- is positioned retroperitoneally on the posterior wall of the abdominal cavity at the level of the second and third lumbar vertebrae.

- has no distinct capsule, but is covered by a thin layer of loose connective tissue.

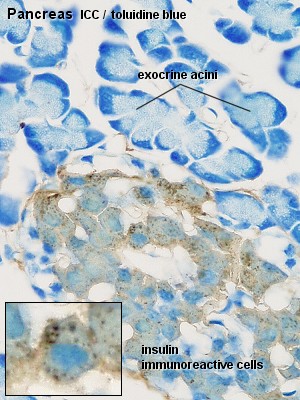

- is both an exocrine and endocrine gland. The exocrine part produces about 1.5 l of pancreatic juice every day. The endocrine part, which accounts for ~1% of the pancreas, consists of the cells of the islands of Langerhans. These cells produce insulin, glucagon and a number of other hormones.

Components of the exocrine pancreas

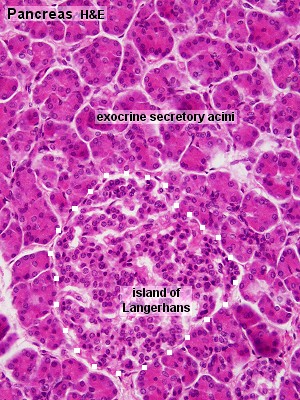

The exocrine pancreas consists of tubuloacinar glands. A single layer of pyramidal shaped cells forms the secretory acini. The apical cytoplasm (towards the lumen of the acini) is filled with secretory vesicles containing the precursors of digestive enzymes. The first portion of the duct system extends into the centre of the acini, which is lined by small centroacinar cells. These cells form the first part of intercalated ducts. Intercalated ducts are lined by low columnar or cuboidal epithelium. They empty into interlobular ducts, which are lined by a

columnar epithelium. Interlobular ducts in turn empty into the main pancreatic duct (of Wirsung), which is lined by a tall columnar epithelium.

The main pancreatic duct opens into the summit of the major duodenal papilla, usually in common with the bile duct. A duct draining the lower parts of the head of the pancreas, the accessory pancreatic duct (of Santorini), is very variable. If present, it may open into the minor duodenal papilla ~2 cm above the major papilla in the duodenum.

Pancreatic juice is a clear alkaline fluid which contains the precursors of enzymes of all classes necessary to break down the main components of the diet:

- trypsin, chymotrypsin and carboxypeptidase hydrolyse proteins into smaller peptides or amino acids;

- ribonuclease and deoxyribonuclease split the corresponding nucleic acids;

- pancreatic amylase hydrolyses starch and glycogen to glucose and small saccharides;

- pancreatic lipase hydrolyses triglycerides into fatty acids and monoglycerides;

- cholesterol esterase breaks down cholesterol esters into cholesterol and a fatty acid.

Proteolytic enzymes are secreted as zymogens - inactive precursors of the enzymes. They are activated in the lumen of the digestive canal. The enzyme enteropeptidase is associated with the brush border of enterocytes. It catalyses the conversion of trysinogen into trypsin. Trypsin can activate a number of the other pancreatic zymogens.

While the enzymes are secreted by the secretory cells of the pancreatic acini, the bulk of fluid and bicarbonate ions of the pancreatic juice are secreted by the cells which form the intercalated ducts of the pancreas.

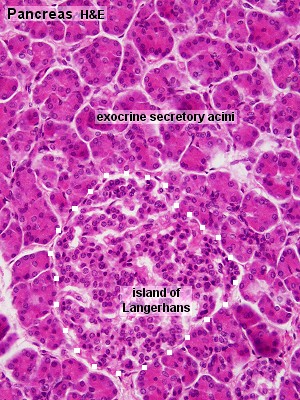

Pancreas, human - H&E

Look at the slide at low magnification and note the subdivision of the pancreas into numerous lobes and lobules. Identify the connective tissue between the lobes and lobules and try to find interlobar or interlobular excretory ducts. Their outline is often irregular and their lumen is lined by a tall columnar epithelium. If you find a large duct you may see a number of smaller ducts streaming towards the larger duct and, occasionally, connecting with it.

The overall appearance of th pancreas is that of a serous gland. At a first glance it may be possible to confuse the pancreas with other serous glands, e.g. the parotid gland. Note that the pancreas does not contain structures resembling the large intralobular ducts of the salivary glands and that the interlobular and interlobar secretory ducts of large salivary glands are lined by ... which type of epithelium?

Draw the excretory duct.

Now have a closer look at the secretory tissue within the lobules. At low magnification most of the tissue appears to be composed of small reddish packages, the secretory acini. Intercalated ducts are difficult to find and so are the initial segments of the (non-secretory) intralobular ducts (cuboidal epithelium). You may try to find them and include them in your drawing, but don't get upset if you or the demonstrators have difficulties locating them.

Draw at the largest magnification a number of exocrine secretory acini. If possible, include in your drawing some centroacinar cells.

Components

of the Endocrine Pancreas

Components

of the Endocrine Pancreas

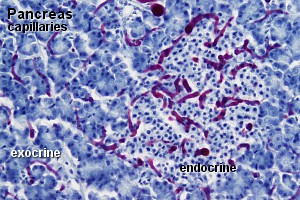

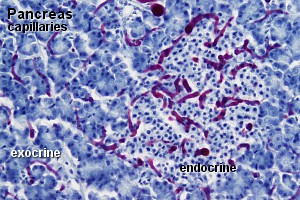

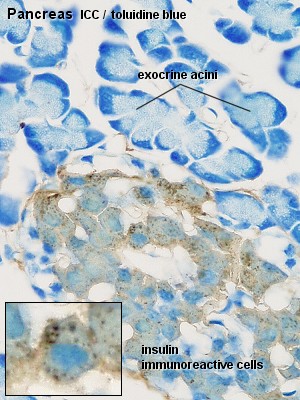

Islands of Langerhans, usually containing several hundred endocrine cells,

are scattered throughout the exocrine tissue of the pancreas. The vascularization,

composed of many fenestrated capillaries, is more extensive than that of the

exocrine tissue.

Although the quantitative cellular composition of the islands is quite variable,

we find typically:

- 75% beta-cells which secrete insulin. Insulin

stimulates the synthesis of glycogen, protein and fatty acids. It also facilitates

the uptake of glucose into cells and activates glucokinase in liver cells.

Beta-cells are fairly easy to recognize in EM pictures because the contents

of their secretory vesicles typically form one or two crystals.

- 20% alpha-cells which secrete glucagon.

The effects of glucagon are generally opposite to those of insulin. The

contents of the secretory vesicles of alpha-cells are fairly electron dense,

and they are typically smaller than those of delta-cells (average of about

300 nm).

- 5% delta-cells which secrete somatostatin, a locally

acting hormone which inhibits other endocrine cells.

- other endocrine cells of the islands secrete

- pancreatic polypeptide, which stimulates chief

cell in gastric glands and inhibits bile and bicarbonate secretion,

- vasoactive intestinal peptide, which has effects similar to glucagon, but also stimulates the exocrine function of the pancreas,

- secretin, which stimulates the exocrine pancreas, and

- motilin, which increases GIT motility.

Pancreas, human - H&E

and Pancreas, rat - ICC

If you scan over the secretory tissue at low or medium magnification, you may be able to identify areas of tissue with a slightly different hue and texture. These areas are likely to represent the islands of Langerhans.

Draw at low or medium magnification a part of the pancreas in which you see an island of Langerhans. Make sure that the difference in texture and/or hue between the endo- and exocrine pancreas is visible (at least to you).

- is the largest gland of the body (about 2% of the body weight in an adult).

- receives both venous blood, through the portal vein (~75% of the blood supply), and arterial blood, through the hepatic artery (~25% of the blood supply).

- is surrounded by a well defined but thin capsule of connective tissue. The connective tissue extends into the liver parenchyma and divides it into the basic structural units of the liver, the "classical" liver lobules.

- functions as an exocrine gland because it secretes bile.

The portal vein, hepatic artery and bile duct enter the liver through the porta hepatis. These three vessels travel together through the liver parenchyma. If one of these vessels gives off a branch it is usually accompanied by branches of the other two vessels. Terminal branches of one of the vessels will consequently be accompanied by terminal branches of the other two vessels.

These groups of three tubes - a branch of the portal vein, a branch of the hepatic artery and a branch of the bile duct - are called portal triads. Portal triads are a key feature of the organization of the liver. Portal triads are embedded in interlobular connective tissue.

The Liver Lobule

An idealized representation of the "classical" liver lobule is a six-sided prism about 2 mm long and 1 mm in diameter. It is delimited by interlobular connective tissue (only little, if any, visible in humans; plentiful in e.g. pigs). In its corners we find the portal triads. In cross sections, the lobule is filled by cords of hepatic parenchymal cells, hepatocytes, which radiate from the central vein and are separated by vascular

sinusoids.

An idealized representation of the "classical" liver lobule is a six-sided prism about 2 mm long and 1 mm in diameter. It is delimited by interlobular connective tissue (only little, if any, visible in humans; plentiful in e.g. pigs). In its corners we find the portal triads. In cross sections, the lobule is filled by cords of hepatic parenchymal cells, hepatocytes, which radiate from the central vein and are separated by vascular

sinusoids.

There are other ways of dividing the parenchyma of the liver into units. Two common ways are divisions into portal lobules and liver acini. Portal lobules emphasize the afferent blood supply and bile drainage by the vessels of the portal triads. The secretory function of the liver is emphasized by the term liver acinus. Acini are smaller units than portal or "classical" liver lobules and relate structural units to terminal branches formed by the vessels of the portal triad but not the portal triad itself. Representations of portal lobules and liver acini vary in different textbooks.

Hepatocytes are separated from the bloodstream by a thin fenestrated simple squamous epithelium, which lines the sinusoids. Between the hepatocytes and the epithelial cells is a narrow perisinusoidal space (of Disse). Contents of the blood plasma can freely enter the perisinusoidal space through the fenestrations of the epithelium lining the sinusoids. Fixed macrophages, Kupffer cells, are attached to the epithelium  .

.

The liver lobule is drained by the central vein, which open into the intercalated or sublobular veins of the liver. These in turn coalesce to form the hepatic veins. They run alone through the tissue, are usually covered by connective tissue and eventually empty into the inferior vena cava.

Adjoining liver cells form the walls of the bile canaliculi  , which form a three dimensional network within the sheets of hepatocytes. Bile canaliculi connect via very short canals (of Hering; formed by both hepatocytes and cells similar to those in the epithelium of bile ducts) to terminal bile ducts (cholangioles) which empty into the interlobular bile ducts found in the portal triads.

, which form a three dimensional network within the sheets of hepatocytes. Bile canaliculi connect via very short canals (of Hering; formed by both hepatocytes and cells similar to those in the epithelium of bile ducts) to terminal bile ducts (cholangioles) which empty into the interlobular bile ducts found in the portal triads.

Liver - H&E and Liver,

rabbit - trichrome & carbon

The Kupffer cell section does not show the detailed organization of the liver

very well. It is however the best section to identify liver lobules. Scan

over the tissue at low magnification and identify lobules. Once you have recognized

them, change to the H&E stained section. It is difficult, if not impossible,

to clearly identify liver lobules in the H&E stained section. The best

indication of a liver lobule are the large central veins and the strands/sheets

of hepatocytes, which seem to radiate out from the central veins. Change to

a higher magnification in the region of a central vein and try to identify

the epithelial cells forming the walls of the liver sinusoids.

Draw a central vein and adjacent sheets of liver cells

and sinusoids. Try to find and draw a portal triad. Identify in your drawing

the branches of the portal vein, hepatic artery and bile duct. Their

size will very much depend on how close you are to the terminal branches of

these structures. Try to avoid the largest portal triads you see.

Liver,

rabbit - trichrome & carbon and Liver - reticulin

Liver,

rabbit - trichrome & carbon and Liver - reticulin

The first slide will allow you to identify the macrophages which adhere to the wall of the liver sinusoids. They are represented by the accumulations of small brown/black dots, the carbon particles ingested by the macrophages.

Draw a spot in which you observe some macrophages.

Have a quick look at the remaining tissue, and try to identify structures you have seen in the H&E stained section. Now take a look at the reticulin stained section, and again identify the structures you saw in the H&E stained section.

Draw a small part of sheets of liver cells and their supporting reticular connective tissue. Include in your drawing some of the hepatocyte nuclei.

Hepatocytes

- make up about 80% of the cells in the liver.

- are typically large polyhedral cells, with large round centrally located nuclei. Hepatocytes are frequently polyploid.

- function in the storage of glucose in the form of glycogen (SER), vitamin A (possibly in specialized lipocytes), vitamin B12, folic acid and iron.

- participate in the turnover and transport of lipids. The synthesis of plasmalipoproteins takes place almost exclusively in the liver (RER/SER).

- synthesize some of the plasma proteins (albumin, α and β globulins, prothrombin, fibrinogen; RER).

- metabolize/detoxify fat soluble compounds (drugs, insecticides; SER).

- participate in the turnover of steroid hormones.

- secrete bile (up to 1 liter per day).

Bile contains both organic components (e.g. lecithin, cholesterol and bilirubin - the latter is a breakdown product of haemoglobin and accumulates in the blood in jaundice) and inorganic components (bile salts). The bile salts facilitate the digestion and absorption of fat in the small intestine.

Many of the components of bile are not secretory products of the hepatocytes in a strict sense. They are reabsorbed in the gut and return to the liver through the portal vein. Here they are taken up by the hepatocytes and excreted again - a phenomenon called enterohepatic circulation.

Terminal bile ducts merge to form interlobular, intrahepatic bile ducts, which eventually coalesce to form first the left and right hepatic ducts and then the common hepatic duct, which connects to the cystic duct and the bile duct (ductus choledochus). The bile duct carries the bile to the duodenum. The cystic duct leads to the gall bladder, where the bile is concentrated and stored.

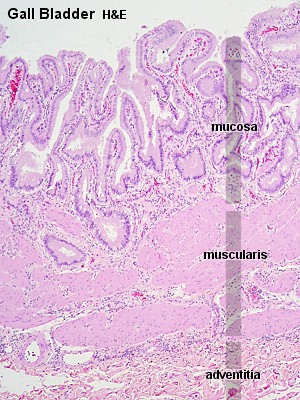

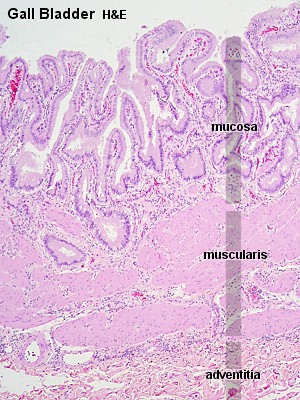

Terminal bile ducts are lined by a cuboidal epithelium. All other parts of the bilary system are lined by a tall columnar epithelium. In the gall bladder the epithelium is often folded and "caved". The epithelium does not contain mucus-producing cells and a muscularis mucosae is absent. These features allow you to distinguish the gall bladder from other parts of the gastrointestinal tract.

Gall Bladder, human - H&E

Have a look at the slide at low magnification. Note the irregular outlines of the epithelium, the relatively dense irregular connective tissue beneath it, and the irregular appearance of the muscular layer of the gall bladder. Now take a close look at the epithelium.

Draw the epithelium and part of the underlying connective and muscular tissues.

Components

of the Endocrine Pancreas

Components

of the Endocrine Pancreas

An idealized representation of the "classical" liver lobule is a six-sided prism about 2 mm long and 1 mm in diameter. It is delimited by interlobular connective tissue (only little, if any, visible in humans;

An idealized representation of the "classical" liver lobule is a six-sided prism about 2 mm long and 1 mm in diameter. It is delimited by interlobular connective tissue (only little, if any, visible in humans;